Gabrielle D. Shaddock, Frida Ballard, Sandie Keerstock & Rajka Smiljanic

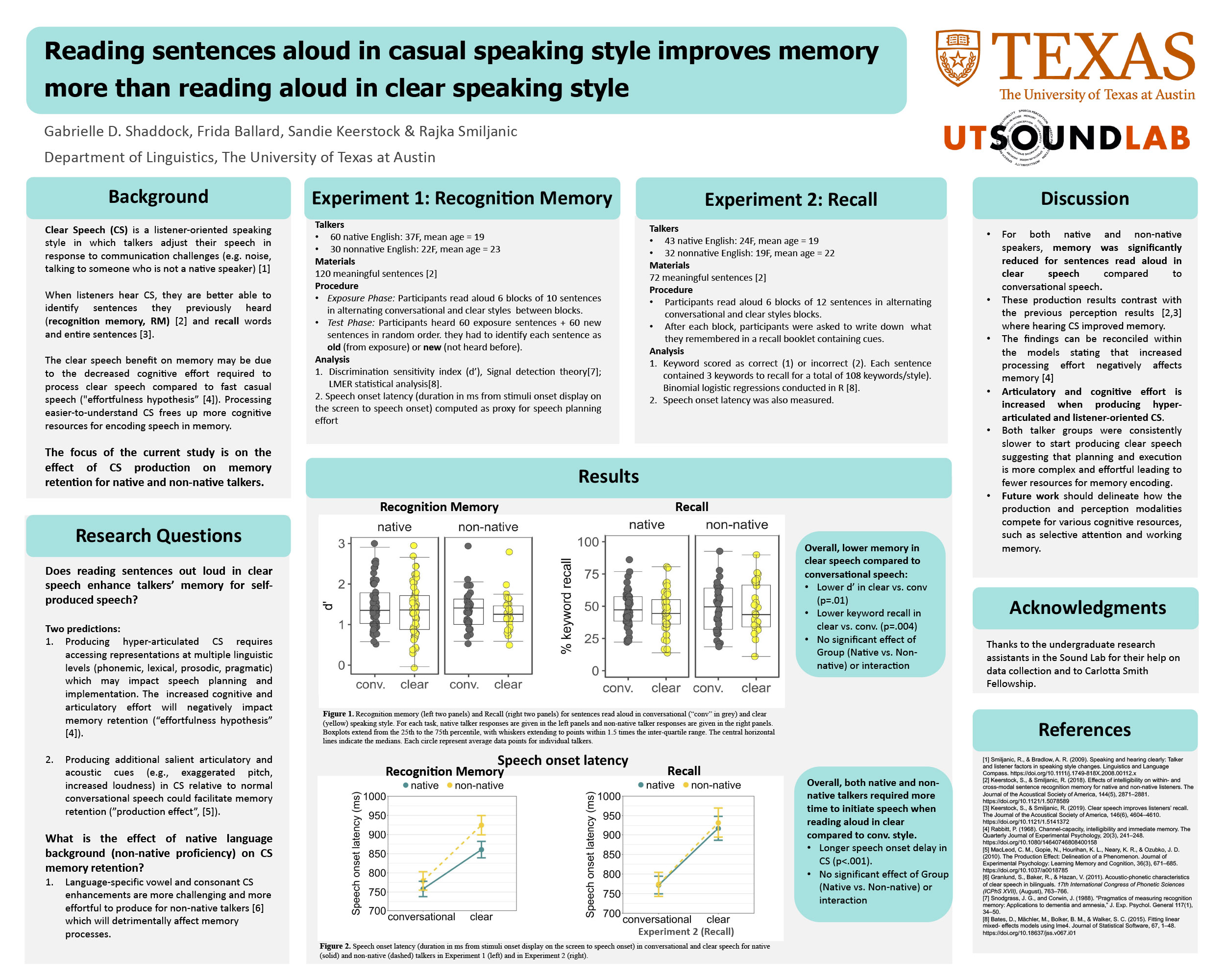

Clear speech is a listener-oriented speaking style aimed at enhancing intelligibility. Clear speech modification may include speaking more loudly and slowly, and carefully enunciating individual vowels and consonants (Smiljanic & Bradlow, 2009). Native and non-native English listeners are more accurate in correctly remembering previously heard sentences (Keerstock & Smiljanic, 2018) and in recalling individual words and entire sentences (Keerstock & Smiljanic, 2019) if the sentences were heard in clear speech compared to conversational speech. This clear speech benefit on listeners’ memory might in part be due to decreased listening effort in perceiving clear speech (“effortfulness hypothesis”, Rabbit 1968). The decreased listening effort may allow the listener to allocate fewer cognitive resources to comprehension for easier-to-understand clear sentences and allow more resources to remain available for encoding spoken information into memory. While the beneficial effect of hearing clearly produced sentences on listeners’ memory is documented, the effect of reading sentences aloud in clear speech on talkers’ memory is unknown. We hypothesized that the effort required to produce clear speech could detrimentally affect memory encoding. In the present study, native and non-native English speakers read sentences aloud in clear and conversational speaking styles. Their memory of the read sentences was assessed either via a sentence recognition memory task (Experiment 1; n=90) or a recall task (Experiment 2; n=75). Results from both experiments showed superior retention of spoken information for sentences read aloud conversationally rather than clearly. The results indicate that producing clear speech, unlike perceiving it, interferes with sentence recognition memory and recall. Production of listener-oriented hyper-articulated speech may recruit more cognitive resources, leaving fewer available for storing spoken information in memory.

Comments

I’m going to apply this to my own studying habits. This is very good poster! – Ethan Roy

Very interesting project! Love how the opposite effect of comprehension and production is so clearly explained by cognitive effort. Does existing literature expand on the potential role of experience? I wonder if people who deliver presentations on a daily basis or TV/radio broadcasters would exhibit less of a production effect between CS and conversational speech. On a different note, I wonder what would happen if you tested your NNs in their native language. Would you predict improved CS memory retention? This might be a surprising find given there was no main effect of group in your present study. Lastly, this is more methodological (sorry if I missed it), other than by instructing the participant to read the prompt in one style or the other, how did you ensure the speech production was clear vs. conversational? I’m curious since you mentioned in your response to Rob that NNSs have more trouble making relevant clear speech contrasts. – Josh

I really like this — really interesting findings, and a cool topic. I’m very interested in the finding that there were no main effects or interactions by language group (this is surprising to me, especially because the task in experiment 2 looks really difficult!). Do y’all have any ideas why that is? Were the non-native speakers highly proficient and/or early arrivals in the L2 environment? – Rob Reichle

Hi Robert, thanks for your comments on the poster! The non-native (NN) participants were very proficient in English: they were recruited from UT so they were proficient enough to be taking classes in their L2, started learning English early at ~age 8, and rated their proficiency as 4.3 out of 5 in English (compared to 4.8 in their L1). Their time of arrival didn’t end up being a significant predictor, though in the analyses, the were more disruptions in memory for the NNs, but not to a significant degree here. Previous studies have shown that NNs have more trouble with making relevant clear speech contrasts, so for someone that is newer to the language and has lower proficiency, we’d expect more memory disruptions and see those differences broaden. – Frida Ballard